The Fading Tradition

It feels like this tradition is disappearing with my generation. My parents might be the last generation to perform ‘Jesa’ (제사), the Korean Confucian ceremony of worshipping ancestors.

In my family, we held rites for ancestors up to my great-grandparents, so we had ‘Jesa’ several times a year. Since my father is the eldest son (Jangnam), these rituals always took place at our house.

As a child, I simply loved those days. All my cousins would gather, we didn’t have to do homework, and we played late into the night. It was just a fun party for us kids.

The Weight of Mother’s Labor

But the moment I discovered my mother’s toil, those days became a burden on my heart. Aside from the meaning of honoring ancestors, for the descendants living in reality—especially the women—it was a negative experience. How can I evaluate tradition? I can’t. But I certainly have the right to evaluate my mother’s hard work. Here is why.

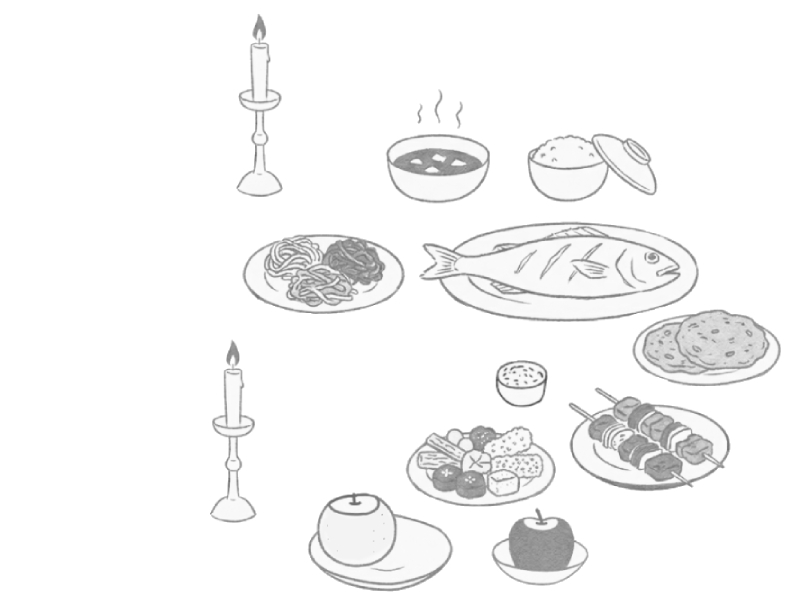

The food preparation begins a week in advance. There are mandatory menu items that must be on the table: Beef soup, rice, dried croaker (Gulbi), skewered meat (Sanjeok), three-color seasoned vegetables (Namul), various pancakes (Jeon), and Bindaetteok. Sometimes, we added special foods the ancestors preferred when they were alive.

My mother never did anything carelessly. She trimmed, cooked, and prepared everything with her whole heart, which required an immense amount of time and effort. On top of that, during major holidays like Seollal(Lunar New Year) and Chuseok, the same table setting and rituals (called Charye) were required.

The Ritual: Hunger and Strict Rules

Jesa was always held at night. We had to skip dinner before the ritual, so we started the ceremony clutching our hungry stomachs.

The table setting begins with reverence and caution. Food is placed on a low, wide table according to strict rules like “Hong-Dong-Baek-Seo” (Red foods on the East, White on the West) and “Eo-Dong-Yuk-Seo” (Fish on the East, Meat on the West). The tops of the fruits are cut off to make it easier for the ancestors to eat. We light incense and candles to signal our location to the spirits.

Once the table is set, the ceremony begins. We rotate the alcohol cup over the incense smoke and place it near the rice bowl. It’s as if the deceased ancestors are sitting right there. We treat them with the utmost politeness using two hands. Then, the men stand in a line facing the table and bow. Not once, but twice.

Amidst rising wisps of incense smoke in a reverence-filled space, offering a deeply devoted bow in honor of ancestors.

The Aftermath: Blessings and Dirty Dishes

When my father, the eldest son, finally says, “It’s over,” it becomes dining time for the descendants. The food offered on the ritual table becomes our late dinner. The ceremony always ended late at night.

And then, the reality hits. Did we truly accumulate ancestral blessings as high as that stack of dirty dishes?

On holidays like Seollal, this ceremony happens in the morning. The ancestors eat first, and then the descendants eat.

My Own Way of Remembering

To be honest, holding rites for ancestors I had never even met didn’t really touch my heart.

With the rise of nuclear families and growing individualism, the rigid and burdensome formalities of these rituals are naturally fading away. While the situation varies from family to family, the tradition of strict ancestral rites is gradually disappearing.

Even if these traditions eventually disappear, I would still set the table with all my sincerity whenever I want to remember my loved ones. It would be a personal ritual featuring their favorite foods—a quiet, meaningful way to meet them again with my heart.